— Where Nishida and Bashō Cross Paths

🌿🍂🪨

In Western philosophy, there is a famous phrase:

“I think, therefore I am.”

But what if the ground of being is not thinking,

but being-with?

The Japanese philosopher Nishida Kitarō, well-versed in modern Western thought,

felt a deep discomfort with its core assumptions.

He was uneasy with utilitarianism, Enlightenment rationalism, materialism, and the Puritanical emphasis on moral productivity—

all of which rest on a logic of separation:

subject vs. object, means vs. ends, self vs. other.

Nishida tried to overturn this logic by asking:

What if we are not isolated individuals analyzing the world,

but already participating in it as expressions of a shared space?

He called this field of mutual arising the basho—the “place.”

Not a physical spot, but a lived space where distinctions dissolve.

🍃

This idea is not abstract in Japanese culture.

It has long been alive in tea, in poetry, in silence, in movement.

Take Matsuo Bashō, for example, who said:

“To learn about the pine, go to the pine.”

He didn’t mean to study it.

He meant to become the pine.

To release the self that stands apart and observes.

Unlike Nishida, Bashō had no need to critique Western rationalism—

because he lived before it arrived.

Before the Meiji Restoration, before the language of “freedom,” “reason,” or “self” entered Japanese through translation.

Bashō lived in a time when words still grew from silence.

Where the world had not yet been cut into subject and object.

Where being-with was simply how one lived.

❖ On the Necessity of Background

To understand any culture deeply,

we must enter into its background—

its rhythms, silences, cosmology, and death-thought.

Whether it’s classical music,

where the pause between notes reveals a theology of silence,

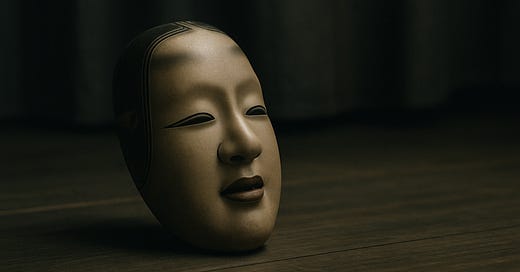

or Noh theater,

where stillness conveys the truth more powerfully than action—

surface alone is never enough.

Even in modern Japanese subculture—anime, manga, games—

what moves people is not just design or storytelling.

It is the lingering gaze of a character,

the silent pause after a line,

the sorrow that is never voiced but always felt.

These expressions still carry echoes of an older ethic:

to live not as an individual operator,

but as part of a shared field of breath, gesture, and time.

❖ The Danger of Surface

Japanese culture often appears beautiful or mysterious to outsiders.

But this is not because of its aesthetic surface.

It is because of a completely different way of relating to the world that pulses beneath it.

When people mimic only the form—without understanding the field that gives rise to it—

the result is not deeper understanding,

but distortion.

In fact, to remain on the surface without listening to the background

can itself be a form of cultural disrespect, even soft discrimination.

It reduces living traditions to consumable “content,”

filtered through modern frameworks of utility, identity, and optimization—

often unconsciously.

❖ Zen and Haiku — Misunderstood Silences

The most striking example is Zen.

Zen is often presented as a technique—

a tool for self-care, focus, or productivity.

But this is not what Zen is.

Zen is not about improvement.

It is not about results.

It is about letting go of the self that wants improvement or results.

To sit in Zen is to dissolve the boundary between you and the world.

No goal. No reward. No escape.

And yet today, Zen is consumed as a “new concept.”

A form of “mindful minimalism.”

This reaches its peak distortion in what is now called Applied Zen.

🧩 Applied Zen is the greatest misreading of all.

It turns Zen into something useful, marketable, effective—

which is precisely what Zen exists to transcend.

It is Zen in vocabulary but Western in logic:

goal-oriented, self-centered, and comfort-seeking.

The same goes for haiku.

Reduced to syllable counts and seasonal words,

its true nature as a poetic form of listening to silence is lost.

Both Zen and haiku are not styles.

They are ways of being.

They arise from cultural, linguistic, and relational backgrounds that cannot be separated from their form.

❖ This is not just about Japan

Importantly, this is not only about Japan.

To understand any tradition—be it Indian dance, Arabic poetry, Celtic myth, or African rhythm—

we must enter the life that gave rise to it.

Its view of death.

Its relation to nature.

Its pace of breath.

To imitate the form without living the background

is to strip the soul from the practice.

This is true of martial arts as well.

When reduced to fighting skills or personal mastery,

we lose the core:

the reverence, the awareness of death, the ethics of gesture,

the training not of the body alone but of being-with others.

🥋 Budo is not about defeating the other.

It is about disappearing into the field with them.

❖ To Understand is to Let Go

Therefore:

To truly understand Japanese culture—or any tradition—

we must first let go of utilitarianism, rationalism, and materialism.

We must let go of the frameworks that ask,

“Does it work?”

“Is it useful?”

“Can it improve me?”

And begin to ask instead:

What is it like to simply live with?

To walk with,

to bow with,

to sit without conquering, naming, or possessing.

❖ Bashō and Nishida — Two Paths, One Place

Bashō and Nishida lived in different eras.

One before the split between language and silence.

The other after the split, trying to mend it.

But both stood in the same wind,

in the same non-separation.

They sought a way of being in the world without owning it.

🪷 Bashō once wrote:

“Sick on the journey,

my dreams wander

the withered fields.”

And Nishida might have answered:

“That field is no longer yours.

It is a shared home.”

🔜

Next Chapter:

Chapter 9 – Shikantaza: When Doing Nothing Becomes Everything

The quiet revolution of just sitting, and the dissolution of the self in pure presence.